In a rather poignant way I feel like life has gone almost full-circle. While developing Decoding Alzheimer’s, I found myself putting off writing my mum’s story. I felt there were no words capable of honouring her life in the way I wanted to; but now I find myself sitting in a coffee shop in Tooley Street in the centre of London, and it feels right that this is where I should start trying to put into words something about the woman who meant everything to me. You see, Mum’s great-grandmother, Mary Ann Price, used to work in a coffee house more than a century ago, at almost the same spot where I’m now sitting enjoying a latte.

I would love to have met Mary Ann. She lived in Victorian London, in the shadow of Southwark Cathedral, across the Thames from the Tower of London and just down the road from Shakespeare’s Globe Theatre. The daughter of parents who could neither read nor write, Mary Ann’s strength of character has become the stuff of legend in our family.

Back in the 1800s, a London coffee house was different from the cafes we know today. It was a place where learned men (yes, women were banned from English coffeehouses!) such as Charles Dickens would go to read, write and talk to like-minded folk about philosophy, science and the politics of the day. It was in the Tooley Street coffee house that the fortunes of our family changed forever. Mary Ann was taught to read and write by the lady owner (something quite unique in those days) and her world was opened up to imagine that life could hold so much more for her and her family.

After suffering the tragedy of losing two husbands at a very early age, Mary Ann emigrated with her third husband and children to what was then, the very young British colony of New Zealand. A move she hoped would give her close-knit family better opportunities. The Price family thrived in New Zealand and remarkably Mary Ann went on to live until her 98th year.

That strength of character and fierce closeness and love for family, was passed down through the maternal line from Mary Ann to her daughter, Clara Jessie, her grand-daughter, Hilda Hetty (my nanna), and then to her great-grand-daughter, Jessie Miriam (my mum).

Even though Mum passed away two years ago now, and the only physical reminder I have left of her is a small lock of hair, she left behind so many memories – happy, sad, joyful, hilarious, fun, and sometimes even frustrating ones. While Alzheimer’s eventually robbed Mum of her own personal memories, mine of her ebb and flow, merging together to take the shape of a strong, independent, selfless, intelligent, gifted, and above anything else, an incredibly loving and caring woman who I am so proud to have called my mother.

Mum was always so much fun. As one of my cousins once said, she was the kind of aunty every kid wished for. The youngest of four children, Mum grew up on a farm and was given complete freedom to be a child, exploring and having many adventures with her sisters and friends. Mum often spoke of those carefree days and her love of horse-riding, swimming, tennis and the outdoors.

Nanna was a very sophisticated woman who was always very well dressed. She tried to dress Mum in frocks and give her dolls to play with, but Mum had other ideas. She was a tomboy and was often seen in shorts driving the old farm truck, which her father taught her to drive as soon as her feet could touch the peddles.

Evenings were always spent singing around the piano and Mum’s father, Harry, realised early on that his daughter was a highly gifted soprano and nurtured her talents, accompanying her on the piano and teaching her to become an accomplished pianist herself. While Mum was a talented and keen sportswoman in swimming, netball, lifesaving and tennis, it was in music, and particularly singing, where she truly excelled. She was a member of the Select Choir at school and was always eagerly called upon to be the soloist in the school’s musical productions, competitions, charity events and broadcasted recordings.

When my sister and I were writing Mum’s eulogy, we found some of her old school magazines that included the following excerpts about Mum’s various musical performances:

“After much hard work the conductor, Miss Herbert, was ALMOST satisfied, and when the great night came the girls rose nobly to the occasion, and, if reports from far and near are to be believed, the broadcast was a great success. The songs covered a wide range from Elizabethan to contemporary composers – greater variety being possible because of the lovely singing of our soprano Jessie Signal, with accompaniments by the Choir. Her singing of “Fairest of Lands” from “the Sun Worshippers” by Goring Thomas, was the highlight of the broadcast, while the most popular item was her singing of “O Can Ye Sew Cushions” the traditional Scots lullaby, both with choir accompaniment.”

Music was Mum’s life and she made it a huge part of her family’s life too. She broadcast regularly, sang in choral societies and was in great demand as a soloist. When many years later she moved to the UK to support my dad, Peter, she attained the highest qualifications in singing and piano at Trinity College London and the Royal Schools of Music, returning later to New Zealand to become a piano and singing teacher as she brought up her two daughters – me and my sister, Christine. Some of my fondest childhood memories are singing around the piano with Mum, and every night we used to lie in bed listening to her singing and playing the piano.

Life held many challenges for Mum. She lost her beloved father when she was still a teenager, and my sister and I both suffered considerably from ill health. Mum never saw the challenges, but always made the most of a situation for what it was with good humour, poise and incredible strength. Like her great-grandmother, she sacrificed a lot for her family, including what would have most certainly been an international operatic career.

For someone who laughed so much, sang so beautifully, and loved sharing time with family and friends, it felt even more cruel that in the last seven years of her life, Mum was unable to talk. I can still remember the night mum’s diagnosis really sank in. I was home alone, and from nowhere I just started sobbing, gut wrenching sobs that couldn’t be controlled. From that moment on, I carried those sobs around inside me in silence, but they would bubble to the surface every time I went to see Mum in the nursing home. They still catch me out today at the smallest of things. Hearing a song that Mum and I used to sing together, is still always the hardest.

I’ve written over 1,000 words and still barely scratched the surface in saying what I’d like to share about my Mum. However, I think the following sums up everything that Mum meant to us and we meant to her …

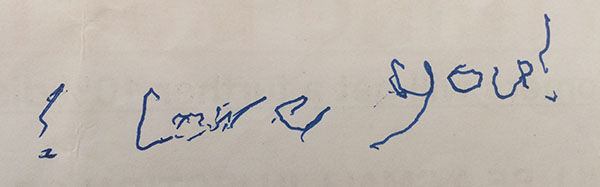

One morning, towards the end of the time when we were able to care for Mum at home, she collapsed and could no longer walk. We had no choice but to get her into hospital and sadly from there Mum went into full-time nursing care as neither Dad nor I could lift her. By this time Mum was also no longer able to talk. I knew she could still understand us and I tried to get her to communicate through writing questions on a piece of paper and prompting her to write a response.

One thing that Mum always used to say over the years when she gave us a hug, or said goodbye, was ‘love you forever’. During those days in the hospital nearly everything she tried to write was indecipherable both in its meaning and because her hands were so shaky, but Mum managed to write this.

Jessie’s story was written by her daughter, Jenny.