When Alzheimer’s is in the top five terminal diseases in the developed world today, why does finding a cure remain so elusive? And why is the disease so difficult to diagnose early enough to slow its path of neurodegeneration? Or prevent its onset in the first place?

One of the main reasons for this frustrating lack of options to treat and prevent Alzheimer’s, is its overwhelming complexity and the diverse nature of the condition. In the same way we differ from each other by just small changes in our genetic code, Alzheimer’s affects everyone slightly differently, and progresses at different rates. Many people living with the disease may also have other disorders, which is referred to as co-morbidity in the medical profession. Conditions such as diabetes or heart disease (cardiovascular disease), or Alzheimer’s in combination with other types of dementia, makes Alzheimer’s difficult to diagnose in its early stages.

We now know that Alzheimer’s doesn’t develop quickly. A single event in the brain (which as scientists we still haven’t isolated) may trigger a cascade of complex changes in the brain that slowly leads to the process of neurodegeneration. Connections between the brain cells (neurons) break down, these connected neurons begin to die, and the brain shrinks in size. These processes of change in the brain can take place over a period of up to 20 years before any symptoms even begin to clinically appear.

Early diagnosis and awareness

Unless we have symptoms, or another reason to suspect we could be at risk of a particular illness, we don’t find any need to visit a doctor for tests. Unfortunately with Alzheimer’s, by the time symptoms such as cognitive impairment begin to show, the disease has already caused potentially irreparable damage to the brain. It is therefore critical to intervene as soon as possible to have any hope of stopping its progression. This is why early diagnosis and awareness is so crucial in our battle to find a way to slow or cure Alzheimer’s.

To develop accurate tests to determine whether someone has Alzheimer’s, we need to first fully understand what causes the disease. Is it for example, the build up of amyloid beta plaques in the brain? Or is it Tau, the other key hallmark protein of Alzheimer’s, that is the main problem? How do these two proteins interact to cause neurons to die? Or does something entirely different trigger the slow process of neurodegeneration?

Research, research and more research

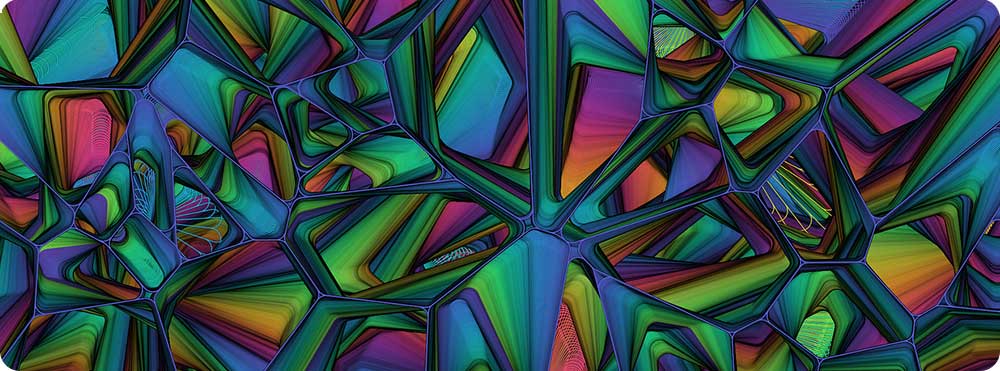

The only way we can answer these questions and tease out what triggers the onset and progression of Alzheimer’s, is through research. And unfortunately, Alzheimer’s is still completely under-funded around the world. Consulting firm, McKinsey and Company presented the following global figures to the World Dementia Council, which shows the glaring difference in the number of researchers funded to work in Alzheimer’s compared to other chronic diseases.

A recent study from Oxford University showed that in the UK dementia research gets 13 times less funding than cancer. For every £10 spent on health and social care, only 8p is spent on research in dementia, while £1.08 is spent on cancer research.

I’m not in any way trying to say that funding should be taken away from any other research. The point to make is that a lot more funding needs to be made available, so we can fund a lot more Alzheimer’s research. Only then will we be able to make advances in our understanding of the disease. Today around two thirds of cancer cases, that have been caught early enough, are treatable as a direct result of better-funded research and through us as the public, demanding it.

The path to drug discovery

Following directly on from this world-wide lack of funding in Alzheimer’s research, there is currently a limited number of drug targets in the pipeline that could help us slow the progression of Alzheimer’s. It is critical that more funds are invested in research to increase the number of potential drugs available for trial, as the clinical trial process is a complex and lengthy one.

You may have already heard through the media at one time or another, that a promising drug for Alzheimer’s has passed Phases 1 and 2 of its clinical drug trial, but then goes on to fail at Phase 3? What does this all mean?

The process

Even before a drug can be considered for a human clinical trial, many years of research have already gone into understanding what drug target might help modify the disease. During this time, as scientists, we will have first developed a hypothesis (question) about what we think causes the disease. In the case of Alzheimer’s, much research has gone into trying to understand the role of the large quantities of amyloid beta (Aß) — one of the hallmark proteins of Alzheimer’s — in the brains of someone living with the disease. The question might ask whether clearing Aß down to the level found in a healthy brain, may improve the cognitive ability of someone who has already been diagnosed with the disease.

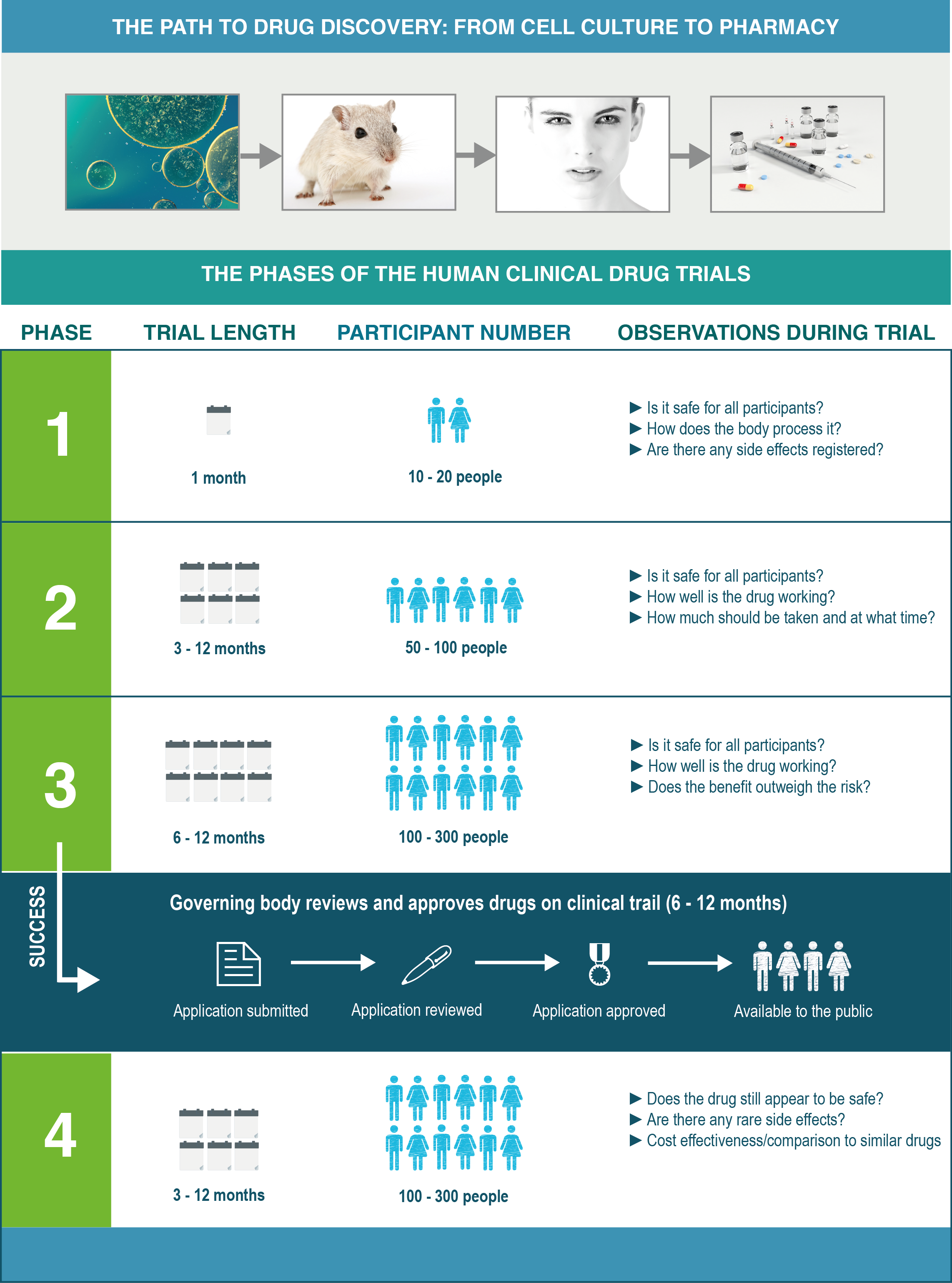

Experimentation generally begins at the cellular level, with cell cultures, and moves up to the organism level, using animal models that are usually mice or rats. When proof is conclusive enough in the mice models, for example, it moves to being worth exploring at the human level, and this is the point when we are ready to consider human clinical drug trials.

An overview of the whole process and what is involved is shown in the figure below, with the trial length and number of people participating in the trial, dependent on the drug and disease mechanism being tested.

We shouldn’t be putting all our eggs into one basket

This process shows just how lengthy the whole path to drug discovery is, in terms of the science. While better funding for researchers is our only hope to advance ways to slow, prevent and eventually cure Alzheimer’s, there is another critical thing we need to be focussing on. To fast-track these goals, it is also crucial to look at investing in more high-risk research approaches that have a greater chance of enabling key breakthroughs, rather than just the incremental low-risk approaches common to many research efforts. As the saying goes, we shouldn’t be putting all our eggs into one basket.